On the 25th anniversary of the First Palaeontomological Conference

Like the majority of insects, time flies. The first International Palaeoentomological Association congress was a generation ago this week, taking place in Russia during the late summer (30th August- 4th September) of 1998. I say 1st IPS congress, but IPS did not exist yet, nor did the International Congress on Fossil Insects, Arthropods and Amber, later known just as Fossilsx3. As recounted by Azar et al. (2013), it was the first general palaeoentomological conference to augment the First World Congress on Amber Inclusions held in Spain that year, later joining the First International Meeting on Arthropodology in Brazil to create Fossilsx3. With the founding of IPS in Poland at the second conference in 2001, the congress as we now know it was born, the next one due in China in 2024.

The First Palaeoentomological Conference was held in Moscow, hosted by the Arthropod Laboratory of the Palaeontological Institute of the Russian Academy of Sciences, a laboratory internationally renowned for its long-established history of palaeoentomological research. More than 70 delegates attended with four days of papers presented covering fossil insects from across four continents, the proceedings being published later in a volume by AMBA Projects in Slovakia. We now have a dedicated journal.

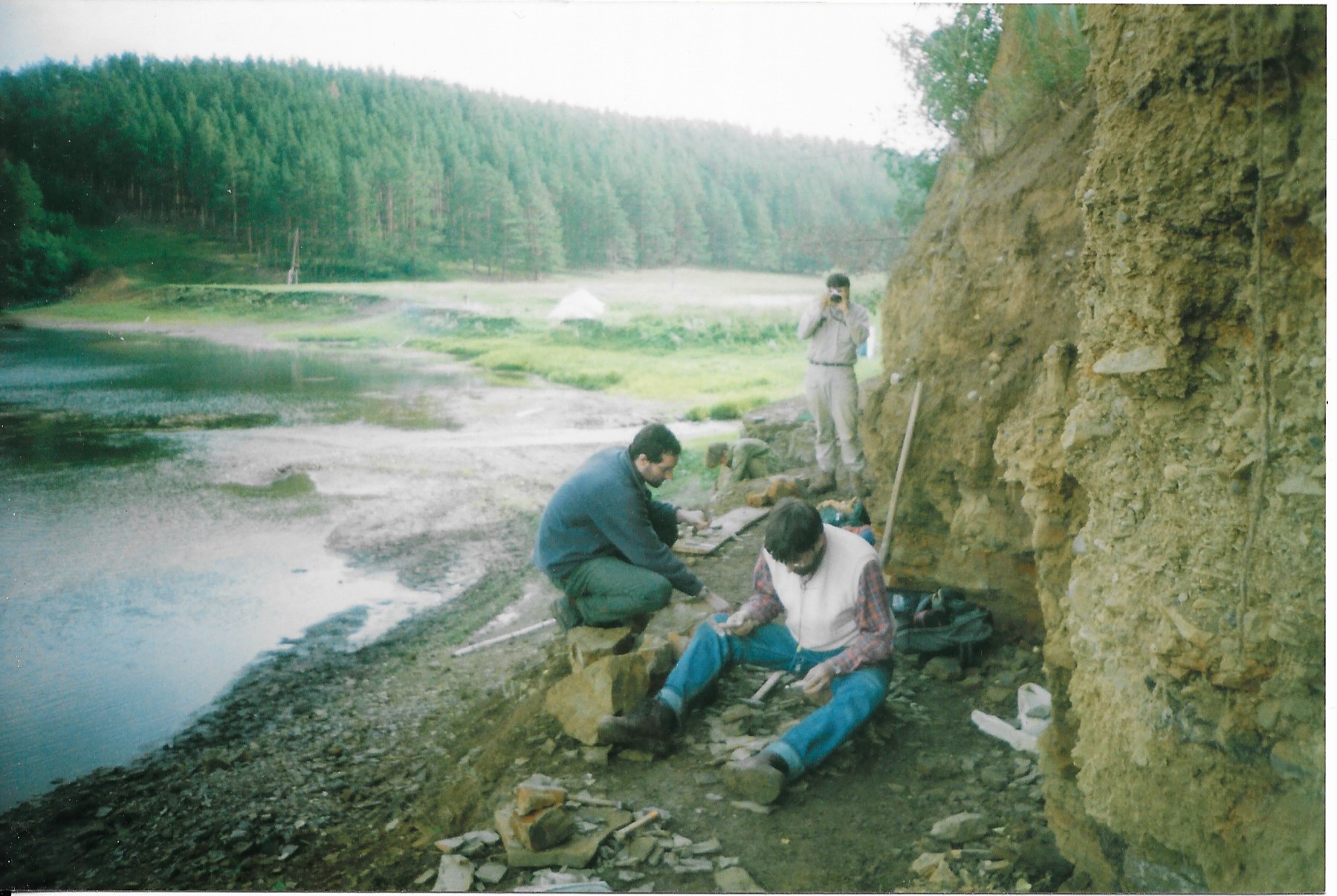

The post-conference fieldtrip to the Lower Permian of Chekarda in the Urals was also a highlight for me as I found my first Permian insects there. The Permian System was recognized in Russia as far back as 1841, after a visit by the Englishman Roderick Murchison, but no Permian insects have ever been found in Britain and Ireland. It was also an opportunity to visit Victor Novokshonov, fossil Mecoptera specialist, at the state university in Perm and show him my new Wealden scorpionflies. Unfortunately, Victor died before actualizing our joint project, which was kindly revived by Alexei Bashkuev and finalised this year (Bashkuev and Jarzembowski, 2023). Chekarda has continued to yield interesting insects, like pollen-bearing Tillyardembiidae, also published this year (Khramov et al., 2023).

Happy Anniversary!

Ed Jarzembowski 29/08/23

In 1990, right after graduating from university, I joined the Palaeoentomology Lab in Moscow. It was during this time that the notion of an international meeting on fossil insects began to take root. The Soviet Union's collapse, Russia's newly opened borders, and the influx of foreign colleagues converged. We even secured one of the first grants for digitizing fossil insects from the European Science Foundation. However, it wasn't until 1996, when Vladimir Zherikhin assumed leadership and quashed the reservations of some colleagues, that we embarked on the project. Despite limited experience, our enthusiasm was boundless.

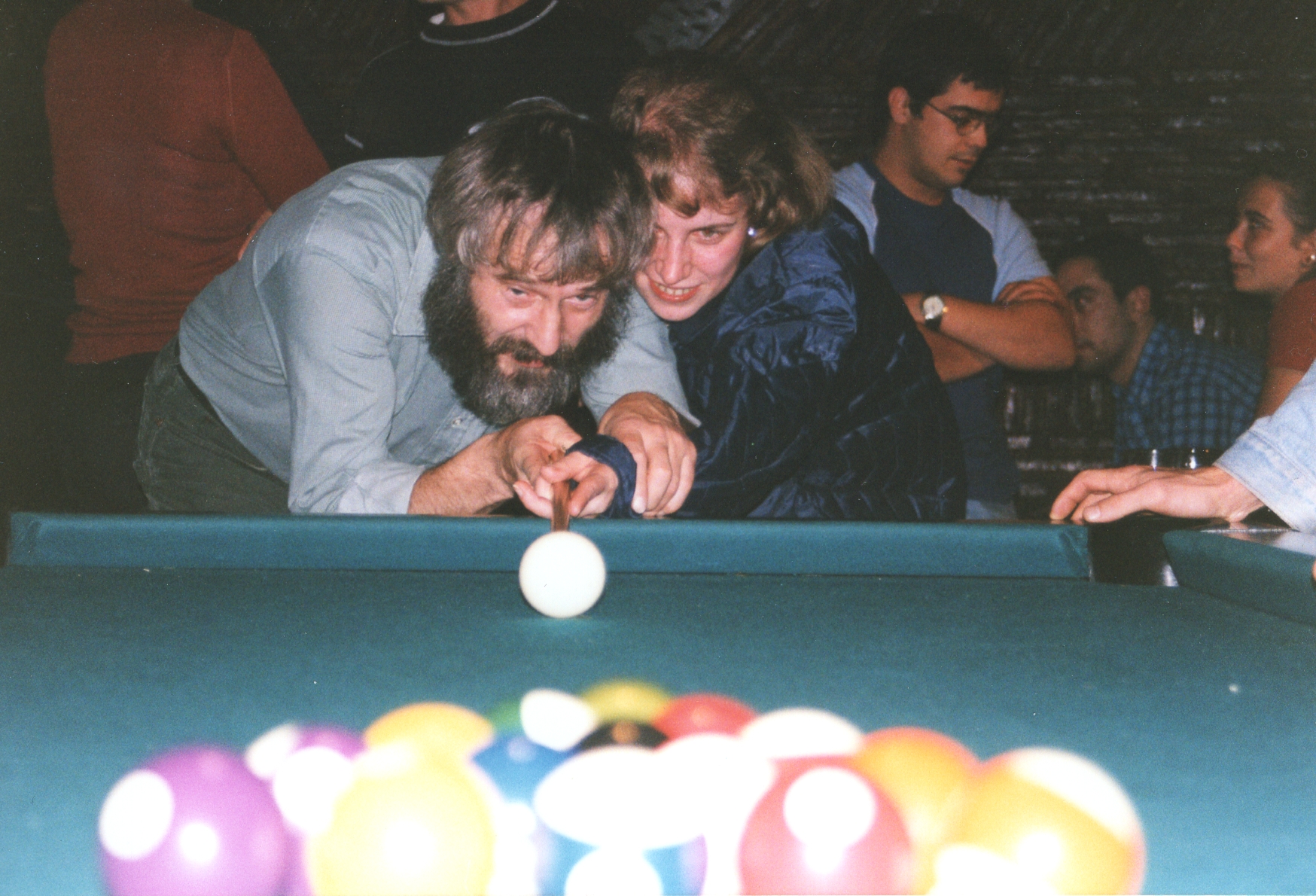

To be frank, my memories of the Conference itself are rather hazy. I believe I attended some talks – I remember Valentin Krassilov and Sergei Golovach performing parallel translation from Russian. However, most of my time, both before and during the conference, was consumed by various bureaucratic tasks. Being the secretary of the Organising Committee, I found myself, alongside Nina Sinichenkova engrossed in activities like reserving venues and accommodations, procuring stationary, printing programs, and even managing currency exchange (a notably daunting task mere days after the rouble plummeted in August 1998). Only on the conference's concluding day could we finally catch our breath, especially during the conference dinner – incidentally held at a Writer's Guild restaurant featured in Bulgakov's masterpiece, The Master and Margarita. The handful of photographs I possess are primarily from that event. Regrettably, some of our colleagues have since departed from this world…

However, it was during those days in Moscow and later in October in Alava, at the International Congress on Fossil Insects, Arthropods, and Amber, that I encountered my most cherished friends and lifelong collaborators. The financial landscape in Russia during 1998 was undeniably challenging, leading me to contemplate a career change. Yet, these twin meetings provided me with a vital revelation: the significance of pursuing one's passion. This juncture profoundly influenced my personal journey, a pivotal moment that unquestionably steered the course of my future life.

Vladimir Blagoderov, 30/08/2023

I was a PhD student when I received information about a congress on fossil insects to be held in Moscow, where some of the most extensive and important collections of fossil insects were located. I decided to attend with great enthusiasm. It would be my first international meeting, although shortly after, I would attend the World Congress on Amber Inclusions in Spain, my own country.

I did not have a scholarship for my PhD, and my income came from temporary contracts in museums. I had to save diligently, and I didn't have enough funds to participate in the fieldtrip to the legendary Permian Chekarda locality after the congress.

I would be the sole Spaniard attending the congress, and I came up with the idea of presenting a paper on all the known fossil insect sites in my country (25 years later, the list has doubled). Obtaining a visa was no easy feat. When I had to travel to Moscow from Barcelona, I visited a large bookstore near Plaza Cataluña... and I accidentally left my document bag containing my passport, visa, and all my money in the bathroom. I was engrossed in the books when a kind stranger tapped me on the shoulder and returned my bag. He recognized me from the restroom and went out of his way to find me.

I vividly recall the enormous two-level airplane; unlike anything I had ever seen before. Meeting my friend Julián Petrulevicius in Moscow was a memorable moment, and we remained inseparable throughout the congress.

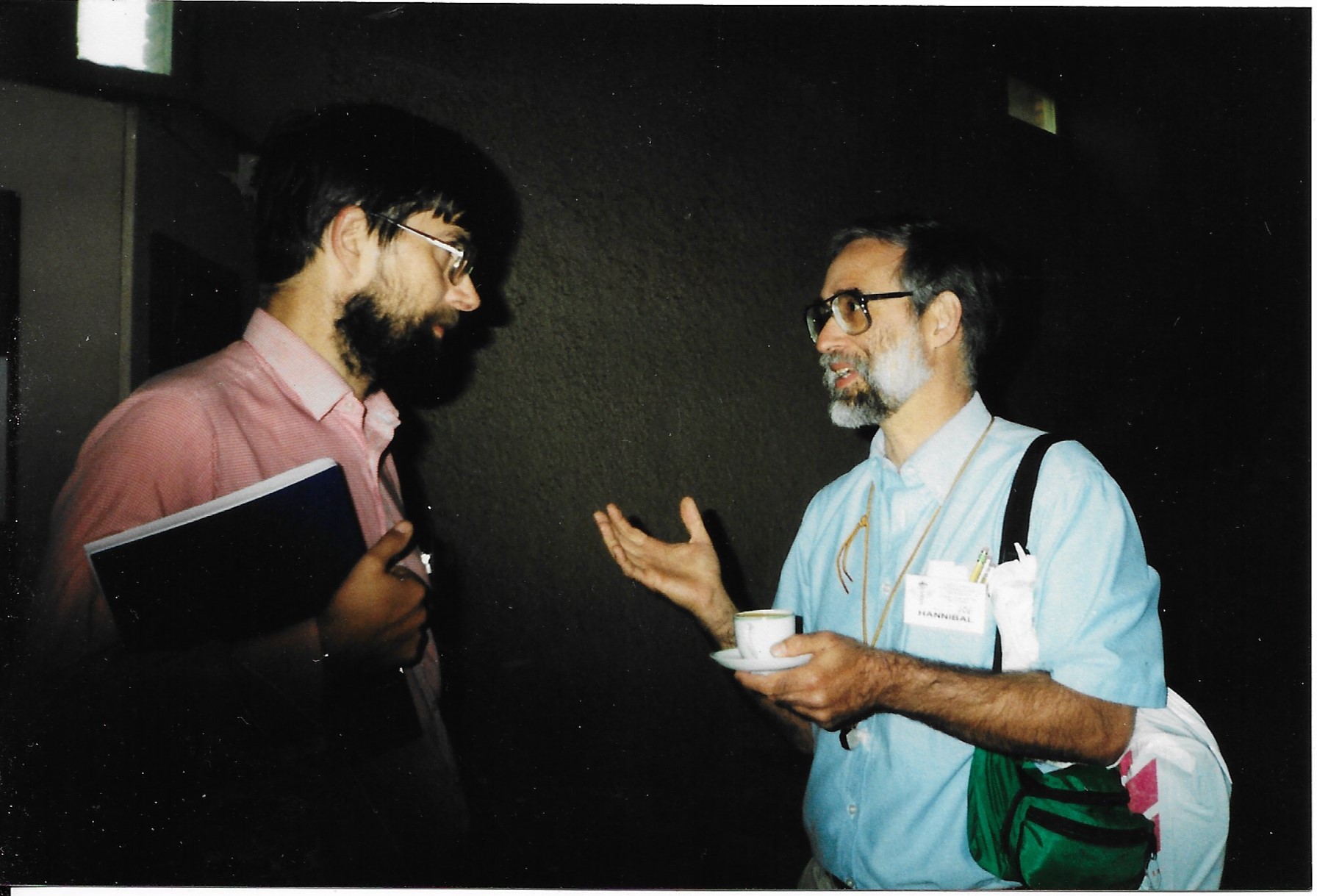

The warm welcome from Russian colleagues, whom I only knew through the publications I kept in my bibliographic folders, was heartwarming. They offered us glasses of vodka, adorned with a chili pepper logo on the bottle. I rubbed shoulders with renowned colleagues such as Zherikhin, Rasnitsyn, Popov, Ponomarenko, Sinichenkova, Krassilov, and others, and they were remarkably approachable in their interactions, much like us Spaniards. I also had the pleasure of meeting colleagues from other countries, including Labandeira, Jarzembowski, Heie, Martíns-Neto, Wegierek, Pinto, Kreminski, and Kreminska.

I have fond memories of numerous delightful anecdotes from those days, including the congress dinner. What I cherished most about the banquet was the fruit arrangement on the table; I had gone days without indulging in fresh fruit, so, without a second thought I went to destroy a piece of art and devour as much vitamins as I could. The night was filled with laughter and enjoyment. At the congress, I forged a special friendship with Vladimir! It seemed like his mission was to ensure that Julián and I didn't find ourselves in any predicaments. Who would have imagined, Vlad, that years later we would reunite in New York for our postdoctoral studies at the American Museum of Natural History? Without a doubt, that congress was memorable and very important for my career as paleontologist.

Shortly after the Moscow conference, in October 1998, the World Congress on Amber Inclusions took place in Álava, Spain. This congress was exclusively dedicated to amber and its bioinclusions. Its inception can be traced back to a serendipitous discovery made by Rafael López del Valle in 1995 - the Cretaceous amber deposits of Peñacerrada. I joined the research on this amber slightly later, recalling the initial stages vividly.

The decision to organize this congress stemmed from the Museum of Natural Sciences of Álava, under the leadership of Jesús Alonso, and the Provincial Council of Álava. Spanish researchers who had been studying Spanish amber, along with numerous paleontologists across the country, enthusiastically rallied behind this endeavor. During the planning phase, we eagerly discussed the names of esteemed international specialists who could be invited or were likely to attend. Many of these experts were unfamiliar faces to us at the time, making this opportunity all the more exciting. Consequently, we had the privilege of meeting and engaging in stimulating discussions with prominent scientists from American, Russian, French, English, Polish, and German institutions, among others. The atmosphere was characterized by camaraderie, and I recall that our "fiesta" often extended late into the night. Even now, I occasionally reminisce about the collection of splendid anecdotes from those memorable days and nights.

Two significant aspects of this congress stand out. First, the exquisite gastronomy of Álava, accompanied by fine wines, added to the overall experience. Second, there was a strong emphasis on daily media coverage, primarily through radio and the press. In my view, this event served as the catalyst for the study of Spanish Cretaceous amber. Over the past 25 years, I am delighted to witness the rapid growth of amber research worldwide, with the Álava congress possibly playing a pivotal role in this development. As I look at photographs from that congress, I recognize some of the colleagues who have since passed away. These reflections on the Álava congress also serve as a tribute to their memory.

Enrique Peñalver 01/09/2023

References

Azar, D., Engel, M. S., Jarzembowski, E., Krogmann, L., Nel, A., and Santiago-Blay, J. 2013. Insect evolution in an amberiferous and stone alphabet. Proceedings of the 6th International Congress on Fossil Insects, Arthropods and Amber, 1-10. Brill, Leiden.

Bashkuev, A. S. and Jarzembowski, E. A. 2023. The first British Cretaceous eomeropid scorpionfly (Mecoptera: Eomeropidae). Palaeoentomology, 6 (3): 255-259. DOI: 10.11646/palaeoentomology.6.3.8.

Khramov, A. V., Foraponora, T. and Węgierek, P. 2023. The earliest pollen-loaded insects from the Lower Permian of Russia. Biology Letters, 19 (3): 20220523. DOI: 10.1098/rsbl.